Milestones in Neural Architecture Search (NAS)

Context (title): Milestones in Neural Architecture Search (NAS)

I recommend a survey (even though it’s mentioned everywhere, I still want to recommend it):

Neural Architecture Search: A Survey

The content is roughly divided into these sections according to the timeline: Miracles with Great Effort, Democratization, Implementation.

1. Miracles with Great Effort

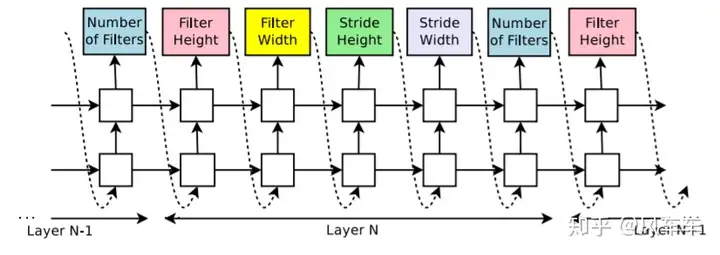

The first well-known NAS work should be Google’s NEURAL ARCHITECTURE SEARCH WITH REINFORCEMENT LEARNING [ICLR’17], which fully showcased Google’s strength and resources (crossed out). The idea is straightforward: previously, the number of filters and their sizes for each layer needed to be manually set, so why not turn it into an optimization problem with several options to let the system choose the best one? These choices combine to form a token encoding a network structure. To make it more flexible and support variable-length tokens, an RNN is used as the controller, and policy gradient is used to maximize the expected reward of the network sampled by the controller, which is the validation accuracy.

Later, these experts might have thought that running CIFAR-10 was too naive and aimed for ImageNet. However, searching directly on ImageNet like before would be unfeasible, not even with 8000 GPUs.

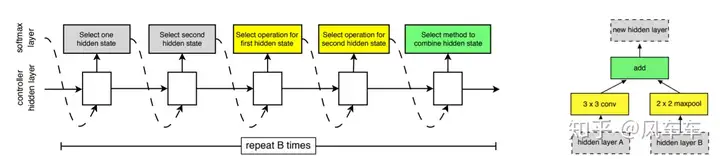

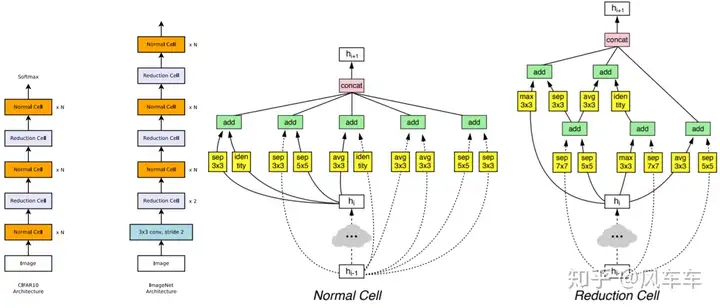

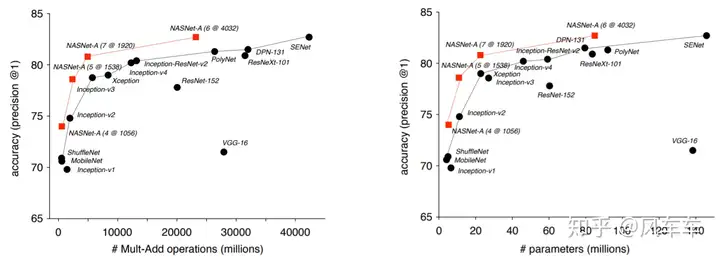

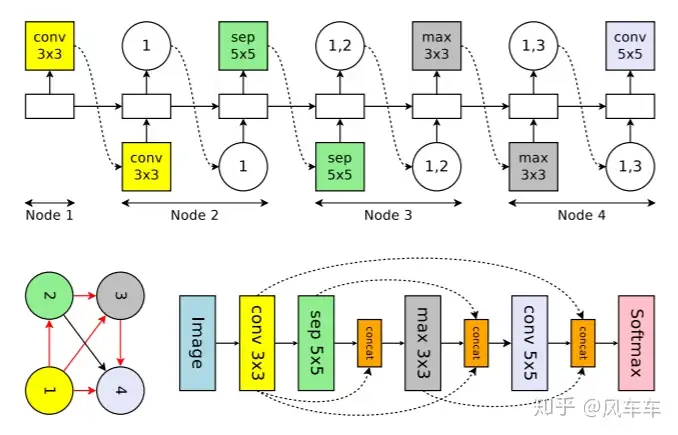

So, Google released another paper Learning Transferable Architectures for Scalable Image Recognition [CVPR’18]. Instead of searching the entire structure, they searched for a cell and stacked it, similar to VGG/Inception/ResNet. They continued using RNN and policy gradient to find the best structure in a new search space, searching for cells on CIFAR and stacking them for ImageNet. The search targeted two types of cells: a normal cell and a reduction cell for downsampling, each containing some blocks. The new search space included selecting which operations to use for these blocks and what to use as input. Many subsequent works followed this NASNet Search Space approach.

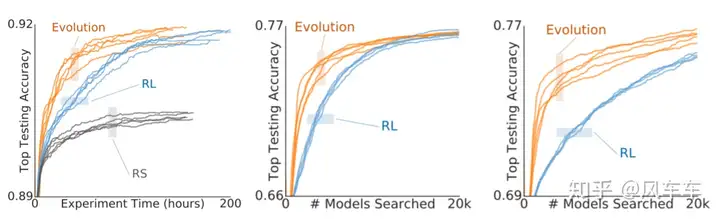

Later, the experts might have thought that since the tokens are now fixed-length, perhaps the RNN+policy gradient optimization method could be replaced with other algorithms (or maybe they found tuning reinforcement learning too frustrating). So, Google released another paper Regularized Evolution for Image Classifier Architecture Search [AAAI’19], using the same NASNet Search Space but replacing the optimization algorithm with regularized evolution (refer to the paper for details… writing it out feels too lengthy (actually just lazy)). The structure found is called AmoebaNet. Experiments showed that evolution is indeed more effective, converging faster, with better results, and less frustrating parameter tuning.

AmoebaNet’s method took 450 GPUs for 7 days, still discouraging…

Later, Google also felt that the previous methods were too time-consuming, so they developed Progressive Neural Architecture Search [ECCV’18], mainly aiming for acceleration. By reducing the search space and using a prediction function to predict network accuracy, the time was reduced to about 225 GPU-days, which is ten times less than AmoebaNet, but still discouraging for ordinary players…

2. Democratization

The “miracles with great effort” approach mentioned above is basically out of reach for ordinary players, but the computational cost problem is evident, naturally leading to some solutions to speed up the process.

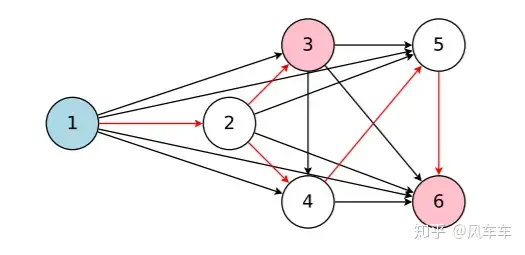

A representative one is weight sharing to accelerate validation in Efficient Neural Architecture Search via Parameter Sharing [ICML’18] (oh, it’s still by Google’s Quoc V. Le and others). The basic idea is to turn the NAS sampling process into sampling subgraphs in a DAG, where the operations (convolutions, etc.) in the sampled subgraphs share parameters. The main difference from previous methods is that in ENAS, the parameters of the subgraphs are inherited from the DAG rather than reinitialized, allowing for validation of subgraph accuracy without training from scratch, greatly accelerating the NAS process.

To evaluate the performance of sampled subgraphs on a dataset, the parameters (weights, etc.) of the DAG need to be optimized. Additionally, to find the best subgraph, the sampler (RNN used here) also needs optimization. ENAS adopts an alternating optimization of the parameters in the DAG and the parameters in the sampler. The optimization of DAG parameters involves sampling a subgraph, then performing forward-backward to compute the gradient of the corresponding operation, and applying the gradient to update the parameters of the corresponding operation in the DAG through gradient descent. The sampler RNN is updated using the previous policy gradient optimization method.

ENAS proposed two modes (only introducing CNN here), one is to search the entire network structure, and the other is to search for a cell and stack it as before. When searching for a cell, it only takes one card for half a day to complete. However, there are many differing opinions on weight sharing in the recent ICLR’20 submissions. Those interested can check openreview.

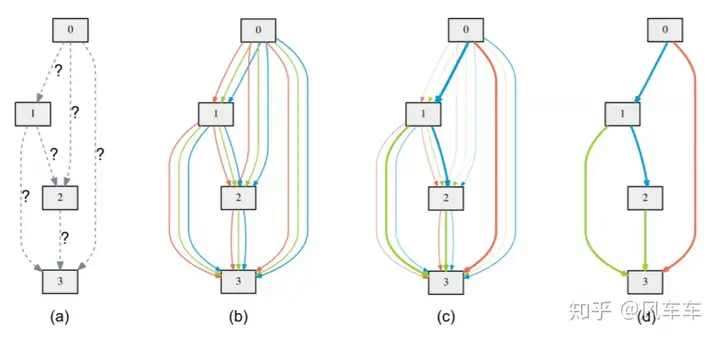

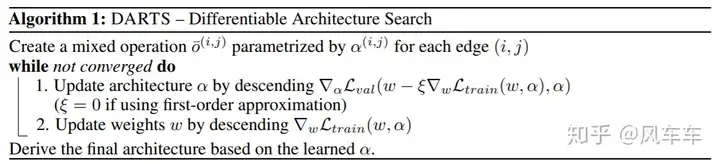

Another NAS work that can be completed quickly uses a differentiable approach for search DARTS: Differentiable Architecture Search [ICLR’19], which has been extensively modified this year (I guess it’s likely because the PyTorch code was open-sourced, and the code is beautifully written, making it easier to modify). DARTS is similar to ENAS, also finding subgraphs from a DAG and adopting weight sharing, with the main difference in the search space and search algorithm. The search space is similar to the NASNet search space, and the search algorithm uses a differentiable approach.

DARTS also searches for cells and stacks them in a certain pattern. The biggest difference in the search algorithm from previous methods is that DARTS does not sample according to the RNN output probability when selecting an operation, but instead sums all operations weighted (not directly weighted, but normalized with softmax) together, putting the weights into the computation graph. After calculating the loss on the validation set, the gradient of the weights can be computed backward and optimized directly through gradient descent. The search process is the process of optimizing the weights, and the operation with the largest weight is the final searched structure.

The optimization of weights and the optimization of weights in the DAG are similar to ENAS, also alternating (optimizing weights on the training set and optimizing weights on the validation set). However, DARTS performs forward-backward on the entire DAG (the downside is that it requires more memory) rather than sampling subgraphs like ENAS.

DARTS only requires one 1080ti to run for a day for a single search, which is no pressure for ordinary players hhhhh.

These two works allow many ordinary players with only a few GPUs to afford NAS.

3. Implementation

The NAS works introduced above rarely show traces of manually designed networks, mostly redesigning new search spaces. From experimental results, the networks found by NAS can indeed achieve good results, but they may not be suitable for practical deployment (e.g., DARTS can achieve high accuracy with a small number of parameters, but the actual forward pass is slow). Since there are already many excellent manually designed network structures, NAS can speed up or achieve better practical deployment performance by introducing these prior knowledge.

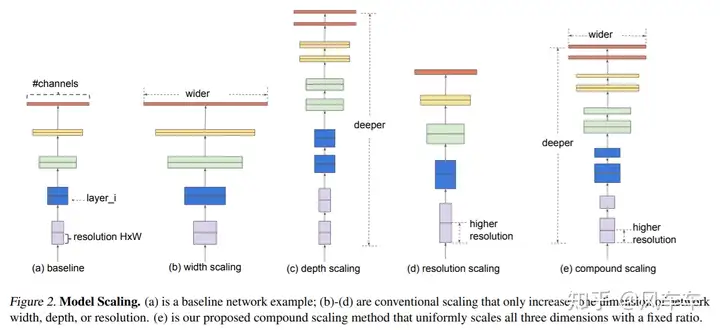

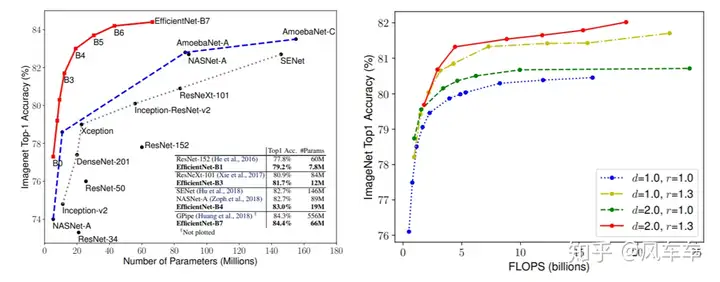

Let’s start with the most straightforward example, EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks [ICML’19], simple and crude. Since MobileNet is fast at the same accuracy, why not scale it up a bit, and see if the accuracy is higher at the same speed? The answer is yes.

The problem is how to scale this network. Simply deepening/widening/increasing resolution has mediocre effects. EfficientNet searched for the relative scaling factors between width/depth/resolution and scaled them proportionally. This approach (which I think also counts as NAS) is simple but effective.

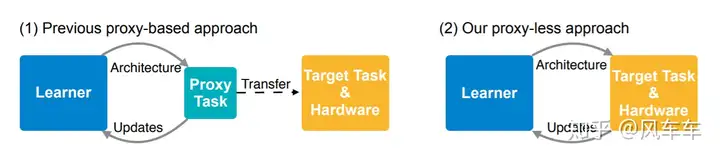

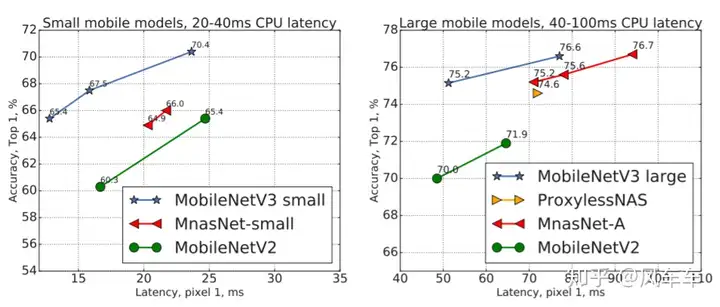

Another work modifying MobileNetV2 comes from MIT’s Song Han group, ProxylessNAS: Direct Neural Architecture Search on Target Task and Hardware [ICLR’19]. The point of this work is not in modifying MobileNetV2 (kernel size, expansion ratio, etc.), but in the proxyless concept. If you want results on a specific dataset and hardware, search directly on the corresponding dataset and hardware, rather than searching on CIFAR-10 and then transferring to large datasets like ImageNet. Additionally, latency loss on hardware is added to the objective function as a multi-objective NAS, directly targeting deployment hardware.

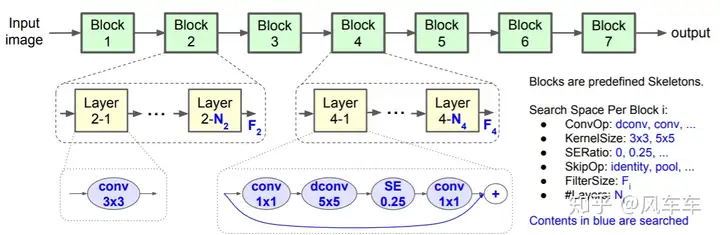

Another series of work also comes from Google, MnasNet: Platform-Aware Neural Architecture Search for Mobile [CVPR’19], used to modify the number of layers/convolution operations/attention in MobileNetV2, and then optimized using the same RNN+policy gradient approach as before.

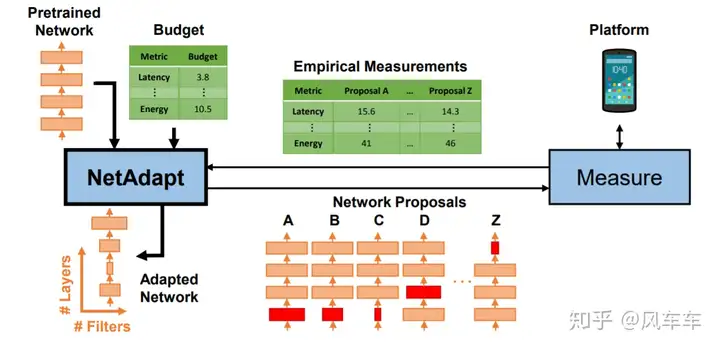

In addition, NetAdapt: Platform-Aware Neural Network Adaptation for Mobile Applications [ECCV’18] compresses existing networks for specific hardware, equivalent to fine-tuning the structure of the network on the hardware.

Google later combined these two works and released Searching for MobileNetV3 [ICCV’19], modifying MobileNetV2 with MnasNet and then fine-tuning with NetAdapt, adding some engineering techniques to get the final MobileNetV3.

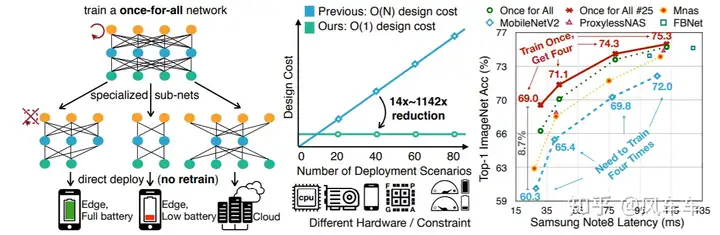

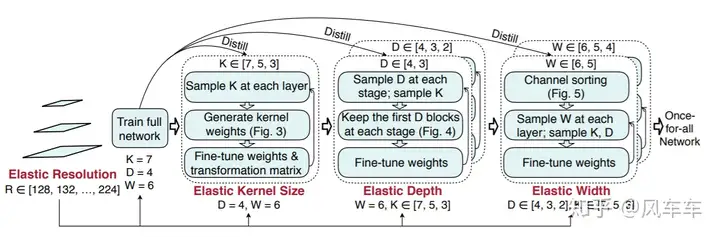

Finally, let’s introduce another recent work from Song Han’s group, Once for All: Train One Network and Specialize it for Efficient Deployment [Arxiv], which trains a large network once, and you can directly extract the network you need from it, decoupling the training process from the search process, meaning you only need to train once.

The amazing part is that after training, it can achieve good results without fine-tuning, likely related to the progressive shrinking training method below. If fine-tuned, the accuracy would be even higher. The version on openreview even exceeds MobileNetV3 by 4 points.

It seems like a good approach. Most of the main time in NAS is spent validating/comparing network accuracy, so spending that time training a large network and then selecting the needed small network might be a more efficient/performance-enhancing way. Once for All uses many techniques, and I recommend checking out the original paper.

Lastly, a conclusion from Rethinking the Value of Network Pruning [ICLR’19]: for structured pruning, the accuracy obtained from the Training---Pruning---Fine-tuning pipeline is not as high as training the target network from scratch, meaning the structural design of the pruned target network is actually the most important, which is what NAS is doing. However, when training from scratch is costly, pruning and fine-tuning strategies are also important to maintain original accuracy with as little computation as possible.

Finally finished writing! I will continue to update if I come across interesting papers in the future~